Results

In the AGEhIV Cohort Study we identify various associated medical conditions, also referred to as comorbidities. Comorbidities become more frequent in the advancing age. Furthermore, we study the prevalence of risk factors for comorbidities and impaired organ functioning. Several analyses have been completed so far. We have examined which comorbidities occur more frequently in our cohort, and what risk factors are related to this increased frequency. This has also been examined separately for the different types of comorbidities and organ dysfunctions, such as cardiovascular diseases, arterial stiffness, high blood pressure, and bone density. In addition, we have studied frailty and participation in the labour market.

103 participants from the AMC and 78 participants from the GGD have participated in the neurological AGEhIV sub study. With the data collected in this sub study, we were able to look at the prevalence of neurocognitive (memory) impairment, the value of screening tests in predicting memory impairments, as well as retinal abnormalities of the eyes. Several other analyses are still ongoing.

Prevalence of comorbidities

Several studies have shown that different types of comorbidities occur more frequently among people living with HIV. In the AGEhIV Cohort Study, we study this topic extensively. The aim of the current analysis was to assess the prevalence of these comorbidities, and whether there is a difference between participants with and without HIV, with similar lifestyles. In addition, we were interested in identifying which factors are related to the prevalence of comorbidities.

During the first study visit all participants were asked to indicate whether they have had certain comorbidities in the past (e.g. heart attack, cancer or stroke). We verified this information by consulting either their hospital medical records in the case of participants with HIV, or by contacting their family doctors (GPs) in the case of participants without HIV. The presence of several other comorbidities was assessed by using blood pressure measurements (hypertension), lung function measurements, and blood tests (diabetes and hyperlipidemia) carried out during the first study visit.

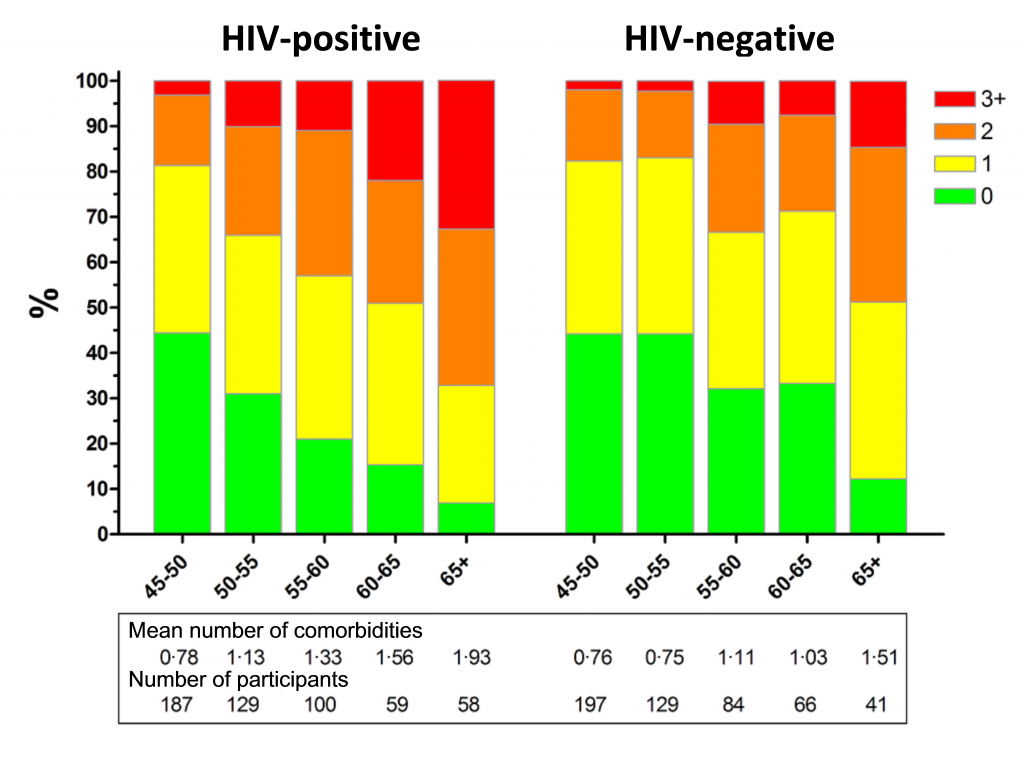

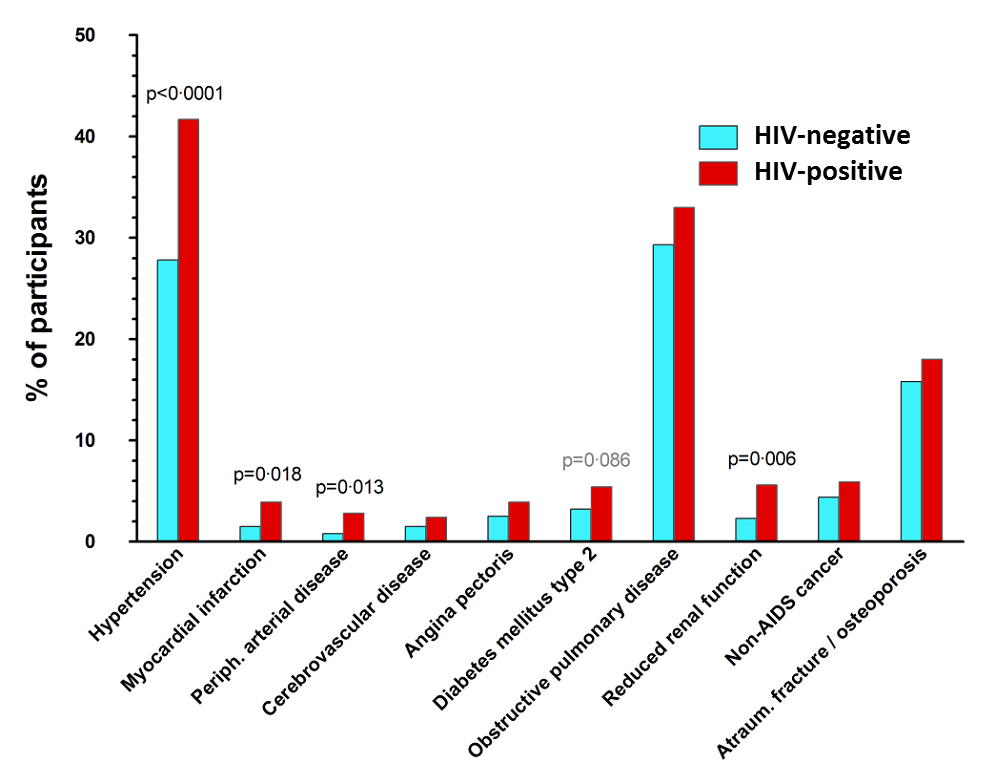

The analysis shows that participants with HIV on average had more comorbidities than participants without HIV (see Figure 1). The comorbidities that occur more frequently among people living with HIV are hypertension, myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease in legs or abdomen and impaired renal function (see Figure 2). Our results suggest that having an HIV-infection is an independent predictor for having more comorbidities. Also, having had prolonged impaired immune function in the past (i.e. immunodeficiency defined as a CD4 count less than 200 cells per milliliter of blood), signs of a stronger inflammatory response measured in blood samples, and the use of high dose ritonavir (Norvir) were all separately associated with higher frequencies of comorbidities.

With the follow-up study visits, we aim to assess whether the differences in comorbidities between participants with and without HIV persist or increase even more, and which risk factors are related this difference.

Learn more about this topic? Click here

Cardiovascular Disease

Various studies have shown that cardiovascular disease is common among people living with HIV. The AGEhIV Cohort Study has done extensive research regarding cardiovascular disease. All study participants have indicated in the questionnaire whether they have had a myocardial infaction, stroke, peripheral artery disease in legs or abdomen, or chest angina in the past. We verified the exact diagnosis in participants’ medical records (of the participants with HIV), or by contacting their GP (of the participants without HIV).

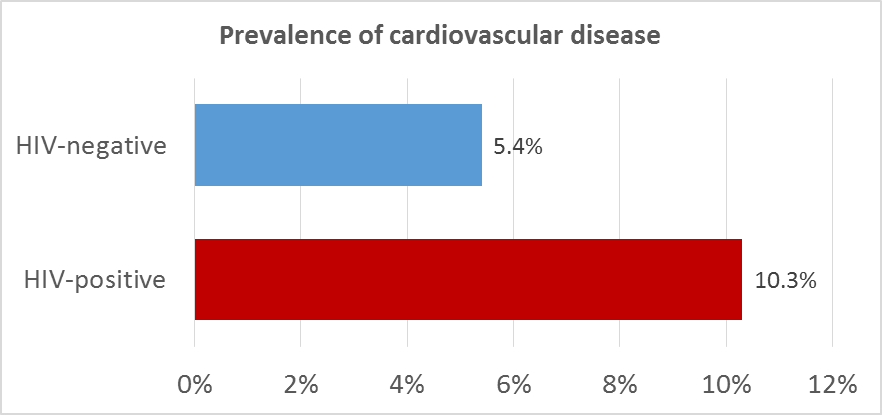

The results show that participants with HIV had a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease compared to participants without HIV (see figure). There is strong evidence that having an HIV-infection is an independent predictor for having had cardiovascular disease, even after taking into consideration known risk factors such as smoking. Prolonged duration of immunodeficiency (CD4 count less than 350 cells per milliliter of blood) was independently associated with the prevalence of cardiovascular disease. In addition, prolonged use of ritonavir (Norvir) in a (nowadays no longer prescribed) high dose (400 mg/day) was associated with the prevalence of cardiovascular disease.

In the analysis, the role of AGEs has been studied in relationship with the prevalence of cardiovascular disease. AGEs (advanced glycation end products) are glycosylated proteins, which can accumulate in tissues. Older age, smoking, and inflammatory diseases lead to increased levels of AGEs. Participants with HIV on average had a higher AGE-value (2.4) than participants without HIV (2.1). The analysis also shows that the increased AGE-value might explain part of the increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease in participants with HIV. This could suggest that AGEs may play a vital role in the development of cardiovascular disease in people with HIV.

Arterial stiffness

During the AGEhIV study visits the stiffness of the aorta has been measured in all participants using the Arteriograph®. The Arteriograph procedure is similar to a blood pressure measurement, and is performed using a cuff around the upper arm. The difference is that the cuff is more strongly inflated than during a conventional blood pressure measurement, in order to estimate the blood flow in the aorta. The stiffer the aorta is, the faster the blood flow. Aortic stiffness may indicate damage to the vessel wall, such as atherosclerosis. Increased arterial stiffness is related to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

In this study, we investigated whether arterial stiffness differs between participants with and without HIV, and aimed to identify factors related to an increased arterial stiffness.

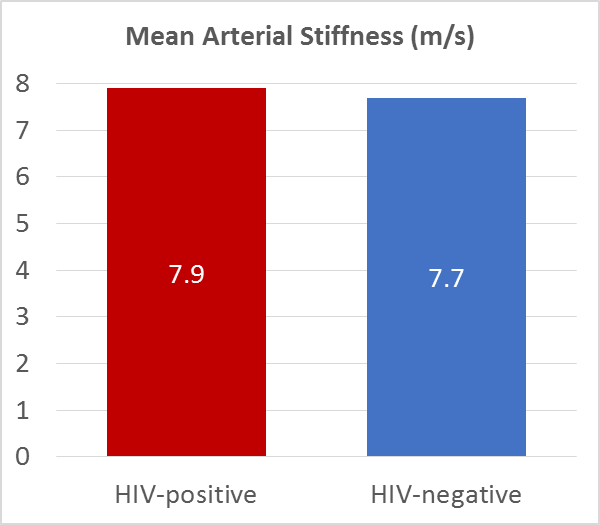

Arterial stiffness measurements obtained in the first study visit showed that individuals with HIV had a slightly higher blood flow (and hence increased arterial stiffness) than individuals without HIV. However, the difference in arterial stiffness is very small: pulse wave velocity was 7.9 m/s in participants with HIV and 7.7 m/s in participants without HIV.

We hope to better understand the risk factors associated with increased arterial stiffness, and the relationship between arterial stiffness and the onset of cardiovascular disease through long-term follow-up of AGEhIV study participants.

The results also showed that cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for an increase in arterial stiffness. In addition, people with HIV who have had serious immune deficiencies in the past (i.e. CD4 counts below 100 cells per milliliter of blood) in particular had an increased aortic stiffness. This may indicate that these patients have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Learn more about this topic? Click here

Hypertension

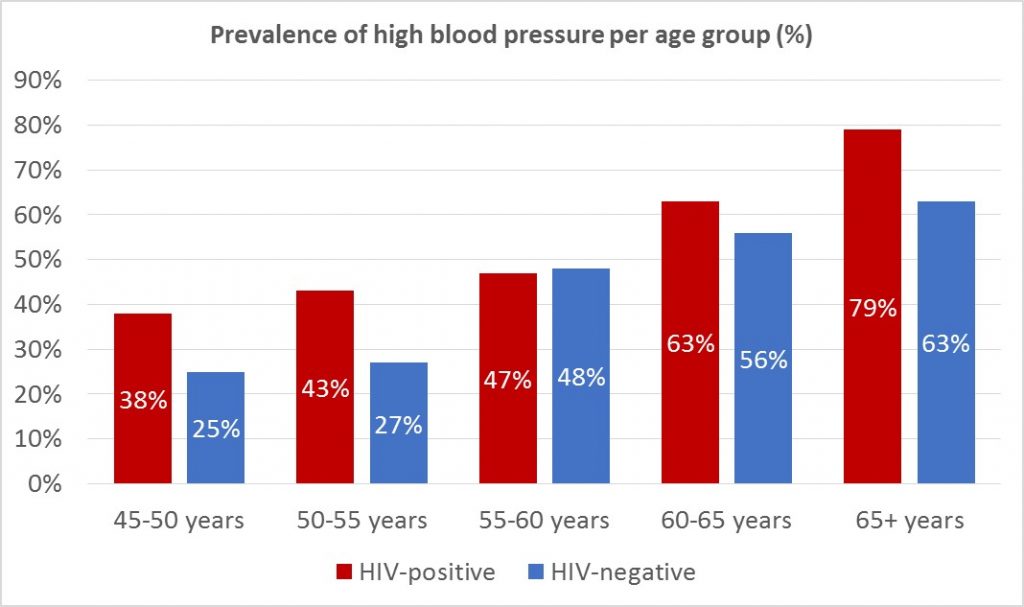

Hypertension (i.e. high blood pressure) is a major risk factor for the development of cardiovascular diseases. During each study visit blood pressure measurements were carried out in all participants, and use of antihypertensives was identified via a questionnaire. Based on this information, we have assessed the prevalence of hypertension in participants with and without HIV, as well as factors that were associated with the prevalence of hypertension.

Data obtained during the first study visit show that hypertension was more prevalent among participants with HIV in the AGEhIV Cohort Study (see figure).

Several factors play a role in the development of high blood pressure, including smoking, alcohol abuse, familial predisposition, insufficient physical activity, and obesity. The higher prevalence of hypertension among participants with HIV seemed mostly due to a larger waist-to-hip ratio in this group. This could partially be the result of the use of specific toxic antiretroviral drugs (stavudine) in the past.

We are interested to see whether there is an increase of the frequency of hypertension in participants with and without HIV in follow-up study visits.

Learn more about this topic? Click here

Bone Mineral Density

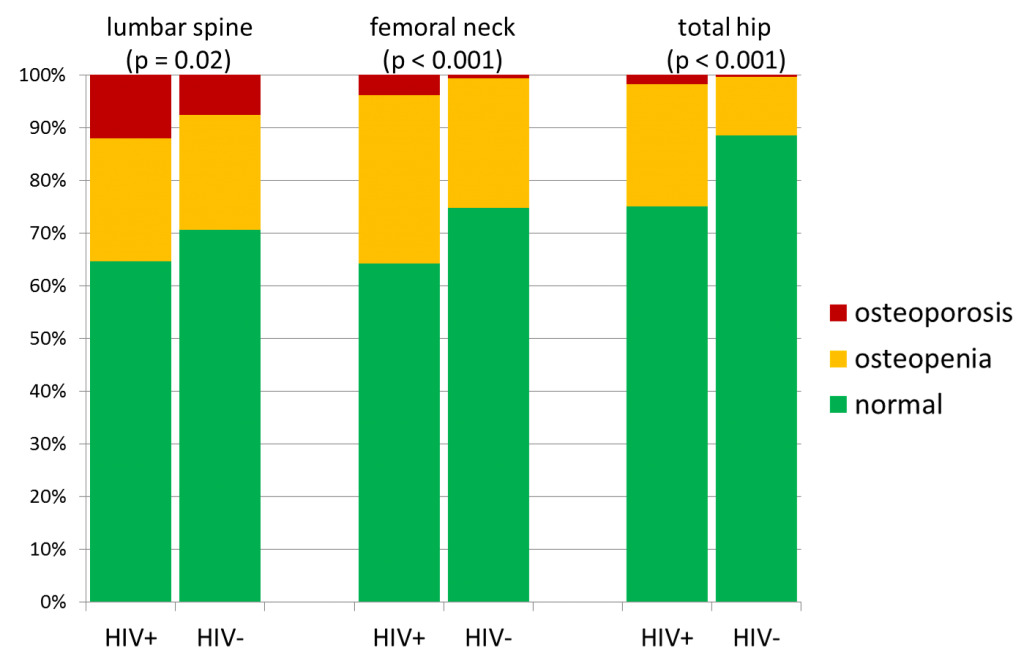

In all participants bone density was measured with the use of a DEXA scan. Bone density in the lumbar vertebrae (the lower spine), the upper part of the femur (upper leg bone) and the femoral neck were all measured. From the analysis of the measurements taken during the first study visit we found that osteoporosis (a greatly reduced bone density) and osteopenia (slightly reduced bone density) are both more common among participants with HIV in the AGEhIV Cohort Study (see figure). Osteoporosis can increase the chance of a fracture.

Two important risk factors for osteoporosis are a low body weight and cigarette smoking. It seems that the frequent occurrence of osteoporosis among the participants with HIV is mostly explained by the fact that a large part of the group smoked and had an – on average – lower body weight. The group that seems to face an additional risk is the group of participants with HIV who have previously gone through severe HIV diseases (such as AIDS) and currently have a lower body weight.

We are very interested to know the results of the following study visits, in which we hope to examine whether the change in bone density over time for participants with and without HIV is different.

Learn more about this topic? Click here

Frailty

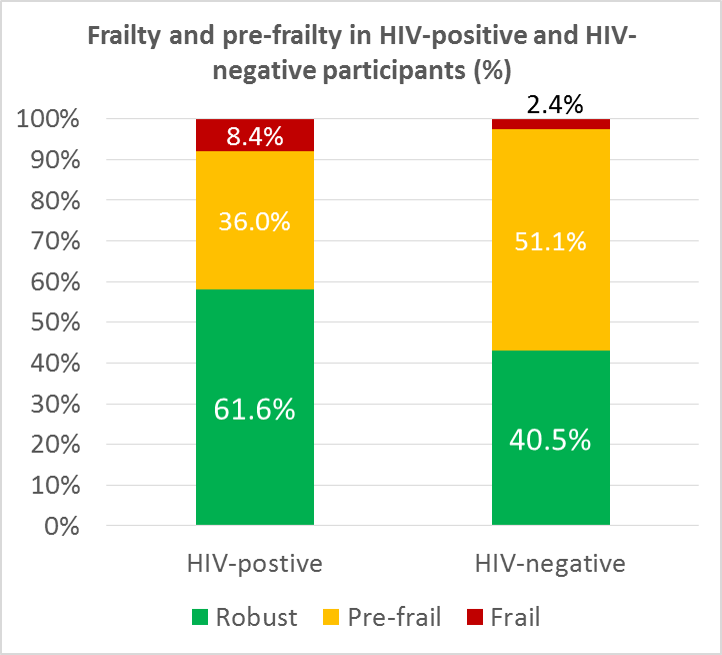

All study participants answer questions during the study visits on unintentional weight loss. Also the pin ching force of the writing hand and the walking speed is measured. Together these measurements are combined to determine if someone is “frail”, “pre-frail” or “robust” (not frail at all). In older people (65 years and over) it has been found that frailty is strongly associated with a risk of falling, hospitalization and death.

ching force of the writing hand and the walking speed is measured. Together these measurements are combined to determine if someone is “frail”, “pre-frail” or “robust” (not frail at all). In older people (65 years and over) it has been found that frailty is strongly associated with a risk of falling, hospitalization and death.

From the results of the first study visit it appears that study participants with HIV are more often frail or pre-frail (see bar chart). The relationship between HIV and frailty was independent of other factors that are also related to frailty. Our study showed some of these other factors to be older age, female gender, a chronic hepatitis C virus infection and symptoms of depression. All these conditions are independently associated with frailty. The results indicate that having more abdominal fat and less fat on the hips has been strongly associated with frailty. In people with HIV this can be a manifestation of the lipodystrophy syndrome associated with use of certain antiretroviral medication.

The precise meaning behind frailty in people with HIV, who are often younger, is not yet entirely clear. Regarding this subject, we hope to gain more knowledge during the follow up in the AGEhIV Cohort Study.

Learn more about this topic? Click here

Participation in the labor market

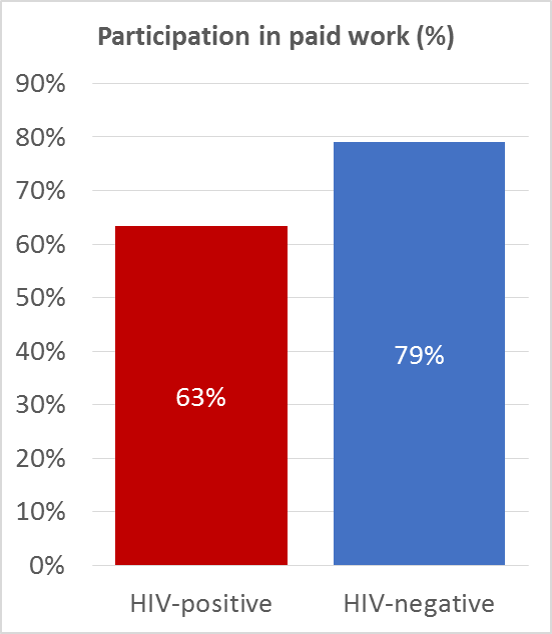

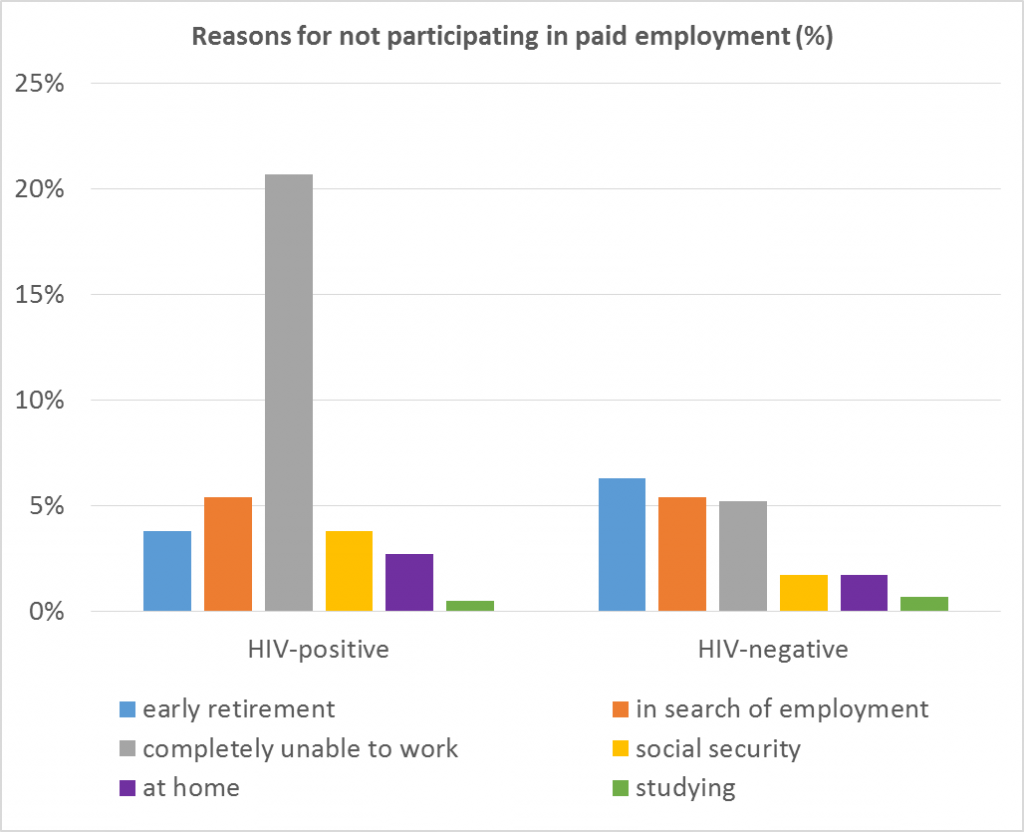

Although people living with HIV are living longer, there is evidence that this group faces age-related comorbidities earlier than people of the same age without HIV. This may have negative consequences for social participation, such as having a job. Among 885 participants of the working age (45-65 years) of the AGEhIV Cohort Study we have looked at the extent to which they participate in paid work, and if working, how their working functionality is.

We found that participation in paid employment was lower among participants with HIV (63.3%) than among participants without HIV (79.0%) (see Figure 1). This difference was largely due to a high percentage (21.7%) of participants with HIV that was completely unable to work. (see Figure 2).

Important factors contributing to being able to participate in paid work were older age, having multiple comorbidities (illnesses) and experiencing stigmas on the workflow.

Among the working participants, we also examined their working capacity; a measure of how well a person can perform in his job. Participants with and without HIV reported the same level of working capacity. This suggests that those living with HIV who did not already have to stop working due to illness, will perform similar to those without HIV.

A diminished working capacity is often reported by those – for example – who have little flexibility to deal with recovery from illness at their workplace, such as being able to plan working hours or holidays freely. Additionally, I appears that having a lower working capacity is also related to having larger work related fatigue and more absence due to illness. People with symptoms of depression, having a part-time job and those born outside of the Netherlands also report lower working capacities.

Learn more about this topic? Click here

Prevalence of cognitive impairment

Before the introduction of antiretroviral therapy, AIDS dementia was one of the most feared complications that could occur as a result of advanced HIV-infection. Despite the currently highly effective treatment for HIV, mild memory impairments (HAND) still seem to be associated with having an HIV-infection. The exact extent of this association remains unclear, as memory disorders occur in both people with and without HIV and could be related to multiple other risk factors as well.

All participants of the AGEhIV neurological sub study underwent a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment. During this assessment six different domains were examined: speech, attention and information processing speed, as well as executive, memory and motor functions.

Results of participants with HIV were then compared with results from participants without HIV with similar age and educational backgrounds. Hereby we determined whether a person was performing below expected levels or not and if the participant could be classified as having HAND (HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders). This classification can be performed in different ways. In the current study, we classified participants using the Frascati criteria, Gisslen criteria and the MNC method.

The estimated occurrence of HAND varies greatly depending on the classification method used. However, whichever method used, results show that HAND is more prevalent among participants with HIV (see figure). After the second study visit, we also hope to make a more elaborate statement about the occurrence of HAND over time.

Learn more about this topic? Click here

Predictors of Cognitive Impairment

Since participants with HIV demonstrated cognitive impairment more frequently, we explored the different factors associated with having HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) or having lower scores during the neuropsychological assessments.

Among participants with HIV we identified seven factors that were associated with a worse score on neuropsychological assessments:

• daily to monthly use of cannabis

• prior cardiovascular disease

• prior decreased kidney function

• diabetes mellitus

• an increased waist-to-hip ratio

• symptoms of depression

• prior low CD4 cell count (severe immunodeficiency in the past)

Four of these factors positively predicted whether a participant with HIV was diagnosed with HAND:

• daily to monthly use of cannabis

• prior cardiovascular disease

• prior decreased kidney function

• diabetes mellitus

This study shows that multiple factors play a role in the development of cognitive impairment in participants with HIV. Part of these factors are related to their HIV-infection, but others are only indirectly or not at all related to their infection.

After completion of the second study visit, we hope to more accurately describe the prevalence of HAND over time and define factors related to its development.

Learn more about this topic? Click here for the published paper or click here for more information.

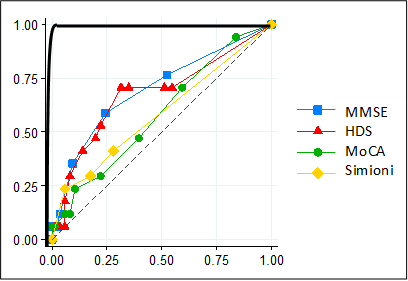

Quality of Simple Memory Tests for the Diagnosis of Cognitive Impairment

A perfectly reliable (hypothetical) screening test is represented by the black line. A completely unreliable (hypothetical) screening test is represented by the dotted line. A real-world good screening test will therefore resemble the pattern of the black line more closely than that of the dotted line.

A screening test is a test that is used to trace down people with a particular disease or condition in a large group of people. In the case of cognitive impairment a screening test could be used to identify those at increased risk for developing cognitive impairment. People that screen positive could then be examined more extensively by means of a complete neuropsychological examination. A good screening test has to meet certain requirements. The central question in this analysis is to determine to what extent some of the commonly used screening tests for memory deficits meet the requirements for identifying those at risk for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND).

In the AGEhIV Cohort Study four different screening tests were studied: HDS (specifically developed for HIV dementia), Simioni questions (consisting of three questions that have been used in trials in mild HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment) MoCA and MMSE (two tests commonly used to screen for other forms of dementia, for example in Alzheimer’s Disease). The results of these screening tests were compared to the results from the extensive neuropsychological assessments performed within participants of the neurological sub study. All screening tests performed moderately to poorly when comparing them with the extensive neuropsychological assesments (see figure). The four screening tests are therefore unreliable and not sufficient to identify HAND, thus not useful for screening in clinical practice.

Learn more about this topic? Click here

Eye examination

Photograph of the retina

Former studies have suggested HIV causes premature aging of the retina. Within an AGEhIV sub study we performed an ophthalmic examination consisting of a number of function tests (e.g. measurement of the contrast sensitivity) and a number of imaging studies of the retina.

All participants have completed their first eye examination and the results have been analyzed. In conclusion, we found no differences in the structure or function of the retina between those with and without HIV. This is good news for the participants with HIV, as a well-suppressed HIV infection seems to prevent changes to the retina.

Treatment of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors

At each study visit, we ask participants whether they have developed cardiovascular disease, for example whether they have had a stroke or a heart attack. We also evaluate whether the participants have risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as high cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, or smoking. Using this information, we have been able to compare whether cardiovascular disease or its risk factors occur more often in people with HIV than in people without HIV. Moreover, we evaluated whether participants were appropriately treated for cardiovascular disease and the associated risk factors. Treatment of cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as the use of antihypertensive drugs to reduce blood pressure to normal levels, is important to reduce the risk of a new cardiovascular event.

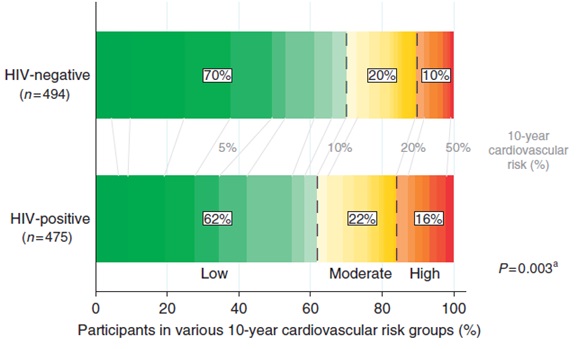

At the first study visit, cardiovascular disease was more prevalent in participants with HIV than in participants without HIV (10% and 5%, respectively). Among the participants with no history of cardiovascular disease, we evaluated the risk of developing cardiovascular disease in the next 10 years. We calculated this risk based on the presence or absence of certain cardiovascular disease risk factors. We found that participants with HIV were more likely to have a high cardiovascular disease risk than people without HIV (figure 1). The most frequently-observed risk factors for cardiovascular disease were insufficient physical activity, smoking, high cholesterol levels, and high blood pressure. These risk factors were more common among participants with HIV.

Figure 1. Estimated 10-year cardiovascular disease risk among participants with and without HIV who had no history of cardiovascular disease.

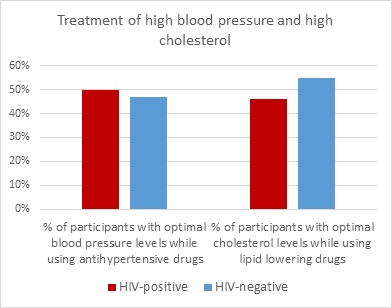

When evaluating whether participants have been adequately treated for their cardiovascular disease risk factors, we focused on those participants at high risk of a cardiovascular event (i.e., those participants who had a history of cardiovascular disease or a high estimated cardiovascular disease risk due to a combination of several risk factors). We found that approximately half of these “high risk” participants had high blood pressure, which, in the majority of the cases, were not being treated with antihypertensive medication. Moreover, over 60% of the “high risk” participants had elevated cholesterol levels, which, in the vast majority of cases, were not being treated with lipid-lowering medication. No significant differences were observed between people with and without HIV.

Next, we focused on participants who used medication to treat high blood pressure or high cholesterol. Approximately 50% of these individuals had optimal blood pressure and cholesterol levels (figure 2). Again, no significant differences were observed between people with and without HIV. However, we did observe that people with HIV who had a history of cardiovascular disease were more likely to use anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs than people without HIV (85% versus 63%).

Figure 2: Percentage of participants who have optimal blood pressure/cholesterol levels while using medication for a high blood pressure/cholesterol.

This study shows that treatment of cardiovascular diseases and associated risk factors is suboptimal, both in people with and without HIV. To prevent cardiovascular disease, a healthy lifestyle and adequate treatment of risk factors for cardiovascular disease are important and therefore require the attention of both patients and their doctors.

Chronic Kidney Disease

At each study visit, we take blood samples and ask study participants to provide a urine sample. We use this material to study kidney function and to look for indications of kidney damage in people living with HIV and those without HIV.

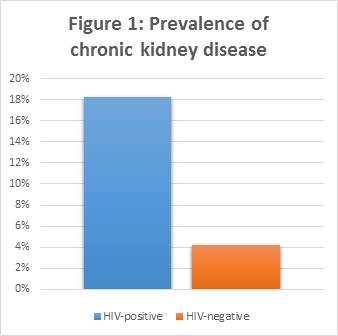

By looking at the levels of albumin in the urine and the levels of creatinine in the blood, we can detect the presence of a reduced kidney function. Our results showed a higher frequency of chronically reduced kidney function in people with HIV compared to people without HIV (figure 1).

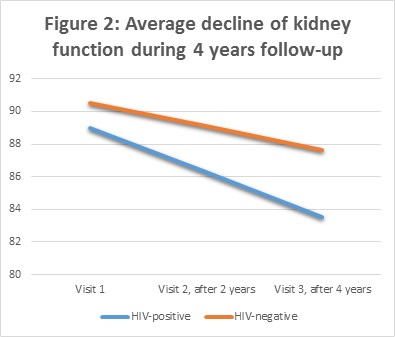

In addition, we studied the course of kidney function over 4 years of follow-up. Kidney function declined in all participants, but we found a stronger decline in people living with HIV (figure 2).

There are several possible explanations for the poorer kidney function observed in people with HIV. First, there are several drugs against HIV (antiretroviral drugs) that are known to have a negative effect on kidney function. One of these is the frequently-used drug tenofovir. Tenofovir is used, or has been used, by a large proportion of the individuals with HIV in the AGEhIV Cohort (73% and 12%, respectively).

It remains unknown whether tenofovir use causes a more rapid decline in kidney function. Our study found no compelling evidence to support this theory. However, since such a large proportion of study participants with HIV use tenofovir, we cannot rule out such an effect. To investigate it further, we would need a comparable group of people with HIV who have never used tenofovir. Unfortunately, we do not have such a group in our cohort.

The results of our study do, however, confirm that traditional risk factors, such as cigarette smoking and hypertension, contribute to a decreased kidney function in people with HIV. Moreover, poorer kidney function in people living with HIV may be due to higher levels of inflammation, which are known to persist in people with HIV despite adequate treatment of their HIV infection.

The older version of tenofovir (disoproxil fumarate tenofovir; TDF) is now frequently being replaced in many HIV treatment regimes by a newer version, namely tenofovir alafenamide (TAF). TAF has fewer negative effects than TDF, including less kidney damage.

Renal function is expressed in milliliter per minute (ml/min)

Cigarette smoking and inflammation

Cigarette smoking increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and premature death. Some studies have suggested that the negative effects of smoking may be worse in people living with HIV than in people without HIV.

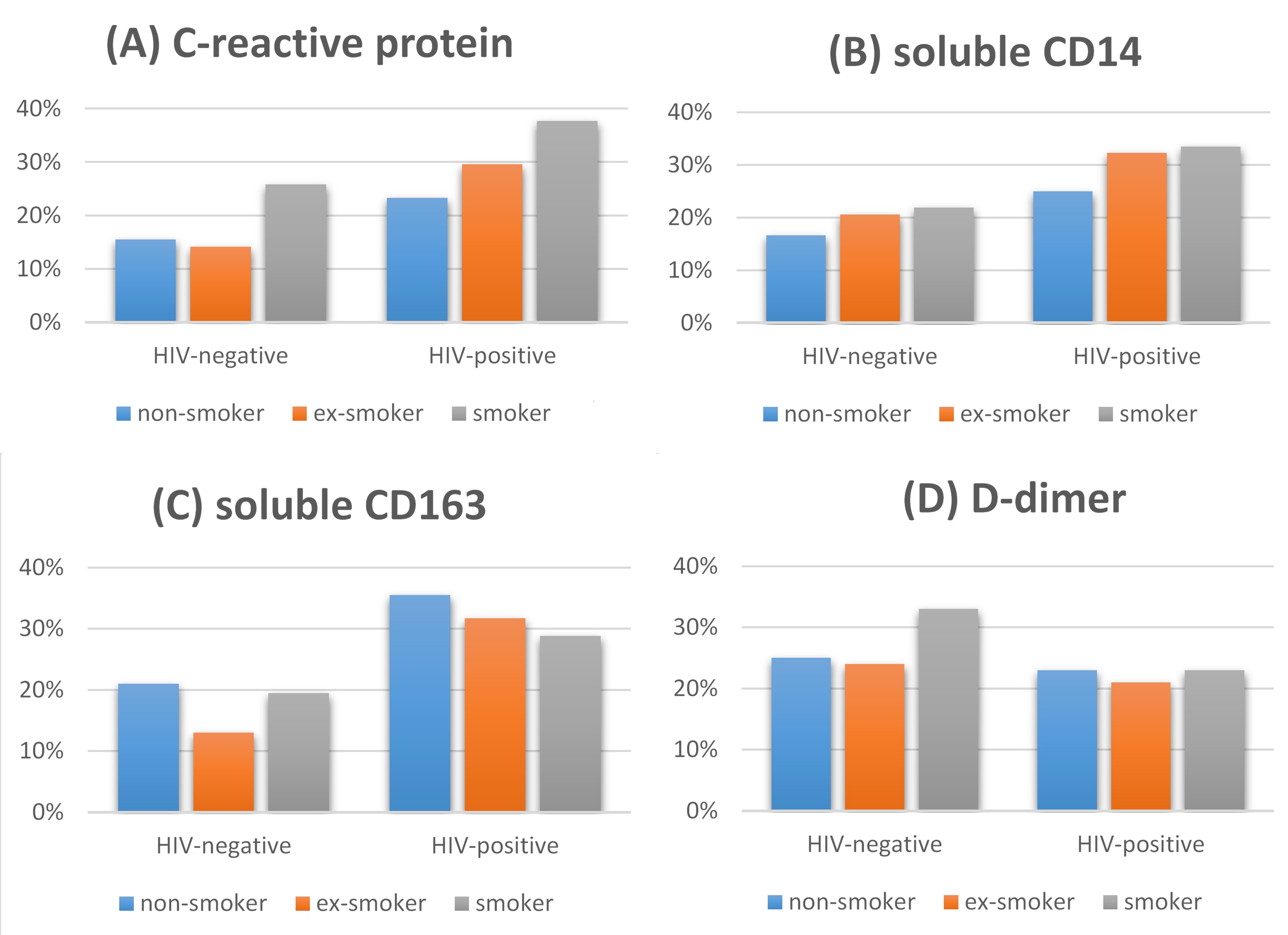

People living with HIV and people who smoke are more likely to have elevated levels of several markers of inflammation. It is thought that this type of chronic inflammation could lead to earlier onset of age-related illnesses, such as cardiovascular disease. In the AGEhIV study we therefore compared the levels of four of these inflammatory markers in the blood of smokers compared with those in non-smokers. In addition, we evaluated whether smoking has a stronger effect on the levels of these markers in people with HIV than in people without HIV.

The markers we studied were C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer, sCD14, and sCD163. CRP is a general marker for inflammation in the blood and D-dimer is a marker for activation of the blood coagulation system. sCD14 and sCD163 are both markers for activation of monocytes, a specific type of white blood cell. Monocyte activation and coagulation may play a role in plaque formation, which may cause cardiovascular disease.

We found higher levels of CRP, D-dimer, and sCD14 in cigarette smokers, regardless of their HIV status. These elevated levels of inflammatory markers likely contribute to the negative health effects of cigarette smoking. We also found higher levels of CRP, sCD14, and sCD163 in people with HIV than in people without HIV, regardless of their smoking status. We found no evidence of smoking having a more marked negative effect on inflammatory markers in people with HIV.

At present, it seems that the reported additional negative effects of smoking on the health of people living with HIV cannot be explained by smoking having a stronger effect on either inflammation or blood coagulation. Further studies are therefore needed to explain this effect.

Proportion of people with a high level (i.e., a value in the upper quartile) of the following markers: C-reactive protein (A), soluble CD14 (B), soluble CD163 (C), D-dimer (D)

Pulmonary (lung) function

Previous studies have shown that the pulmonary function of people living with HIV on average is worse than in people living without HIV. Often this can largely be explained by the on average more extensive smoking of tobacco by people living with HIV.

A very limited amount of studies have looked at the effects of a (well treated) HIV-infection on pulmonary function independent from risk behavior such as smoking. To understand this better the pulmonary function of all AGEhIV participants was measured using a spirometer. Participants were also questioned about their current and previous smoking behavior to be able to take this into account when analyzing the spirometry results. The results from the first spirometry measurements from the first study visits are described here.

Remarkable was that a spirometry-determined decreased pulmonary function was frequently present. An abnormal spirometry result means that too little air is exhaled in 1 second relative to the total lung volume. This was not only frequently observed in AGEhIV participants with HIV, but also in those without HIV. In both groups almost 1 in 4 participants had a spirometry-result that could indicate (early) “obstructive lung disease”, such as asthma or COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). This was an unexpected finding, since participants with HIV were smoking more often. We therefore had expected to see a worse pulmonary function in people living with HIV, simply as a result of their smoking behavior.

We also found that non-smoking participants without HIV more frequently met the criteria for “obstructive lung disease” than non-smoking participants with HIV. We did not however find evidence for HIV potentially having (had) a protective effect on pulmonary function. In fact, our results suggested that HIV has had an effect on the lungs which has made them slightly more rigid, allowing the lungs to hold only a lower total amount of air.

When applying the spirometric criteria for “obstructive lung disease” this results in a seemingly favorable test result. As a result of this impact of HIV on the lungs, spirometry becomes unreliable to determine the presence of “obstructive lung disease” .

Only few conclusions can be drawn from these findings. First, the simple spirometry measurements appear to be insufficient in determining all aspects of pulmonary function in people living with HIV.

Second, the finding that AGEhIV participants without HIV also frequently showed a decreased pulmonary function is potentially due to the lifestyle these participants have had, resembling more the lifestyle of participants with HIV than that of the general population. The participants without HIV are largely STI-clinic attendants and men who have sex with men. It could well be that during their lifetime they on average have visited clubs and bars more often, where for a long time (passive) smoking was ubiquitous. This potentially has had an effect on the pulmonary function of these older men without HIV.

Continuing the spirometry measurements during the follow-up in the AGEhIV study nevertheless remains important, given that studying the changes in the spirometry results over time between participants with and without HIV may provide further insight into the influences of treated HIV-infection on the lungs.

For more information, click here

Lung function change over time

Previous research on lung function at the start of the AGEhIV Cohort Study (see above) indicated that the lungs of participants with HIV may have been stiffer and could contain less air in total. There was no difference in the amount of air that people breathed out in one second (the so-called one-second value), as is, for example, often the case in people who smoke. As a result of these findings, after the fourth AGEhIV study visit, the AGEhIV study group investigated how lung function changed over time in people with and without HIV. Few similar studies have been done.

The main finding was that in participants with HIV (most of whom had a well-suppressed virus), both the total amount of air that the lungs can contain and the one-second value decreased slightly faster than in people without HIV, even if they did not smoke. This might indicate that, even though HIV is well-suppressed with treatment, the virus can somehow continue to damage the lungs. Our study provided some indication that inflammation of the lungs may play a role in this. It is currently unclear to what extent people with HIV will notice this decrease in lung function themselves.

Nevertheless, it is important that doctors and nurses are aware of these findings. In people with HIV and unexplained respiratory symptoms, it can be an additional reason to conduct more lung tests. Regardless of our findings, the advice to stop smoking remains important under all circumstances.

Want to know more? Click here to read the article.

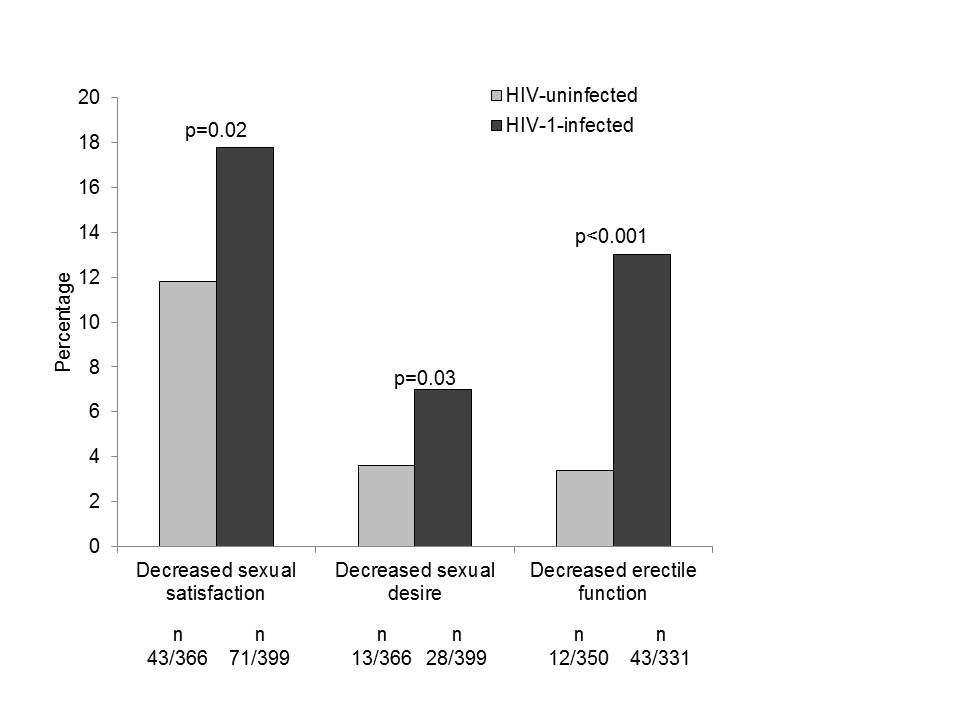

Sexual function

In this analysis we assessed whether people living with HIV experience more sexual problems than people without HIV. The questionnaire which participants complete at each study visit includes questions about sexual functioning. We assessed what men who reported having sex with men had answered to these questions. The questions concerned three sexual domains: erectile function, sexual satisfaction and sexual desire. The responses to these questions revealed that men having sex with men living with HIV experienced decreased erectile function, decreased sexual satisfaction and decreased sexual desire more often than their counterparts without HIV. This could partly be explained by the fact that the men living with HIV more often reported depressive symptoms, had more other diseases and more often used medication for high blood pressure – each of which are all also related to sexual functioning. The difference in erectile function (getting an erection) was most pronounced between the men with HIV and without HIV. Those who were treated for HIV with lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) in the past or at the time of their first study visit more often experienced decreased erectile function. Based on these results, we have expanded the number of questions on sexual functioning in the study questionnaire, so that we can evaluate sexual functioning among study participants in more detail in the future.

For more information, click here

Weight gain integrase inhibitors

In recent years, a number of international scientific articles have been published describing weight gain after starting an integrase inhibitor. Integrase inhibitors (raltegravir, elvitegravir, dolutegravir and bictegravir) are a particular class of HIV medication. This phenomenon was also examined within the AGEhIV Cohort Study by looking at the change in weight in study participants with HIV who – whilst having an undetectable amount of virus in their blood – started an integrase inhibitor. The weight change in this group of participants was compared with participants with HIV without change in medication (and without the use of integrase inhibitors) and with participants without HIV.

There was no difference in the mean weight gain over time between these three groups. However, a small group gained relatively large amounts of weight (>10% increase in weight). This happened slightly more often in people who started integrase inhibitors. This indicated that not everyone gains weight after starting an integrase inhibitor, but some people may be more susceptible to do so.

Dark-skinned women were more likely to gain more than 10% weight after starting integrase inhibitors. Unfortunately, the numbers of women and dark-skinned people in this study were too small to draw definitive conclusions. It is not yet entirely clear why some people are sensitive to gain relatively large amounts of weight when taking integrase inhibitors – hereditary factors may play a role. This is currently being investigated further in other research groups.

If you are interested in the publication, please click here.

The development of comorbidities over time

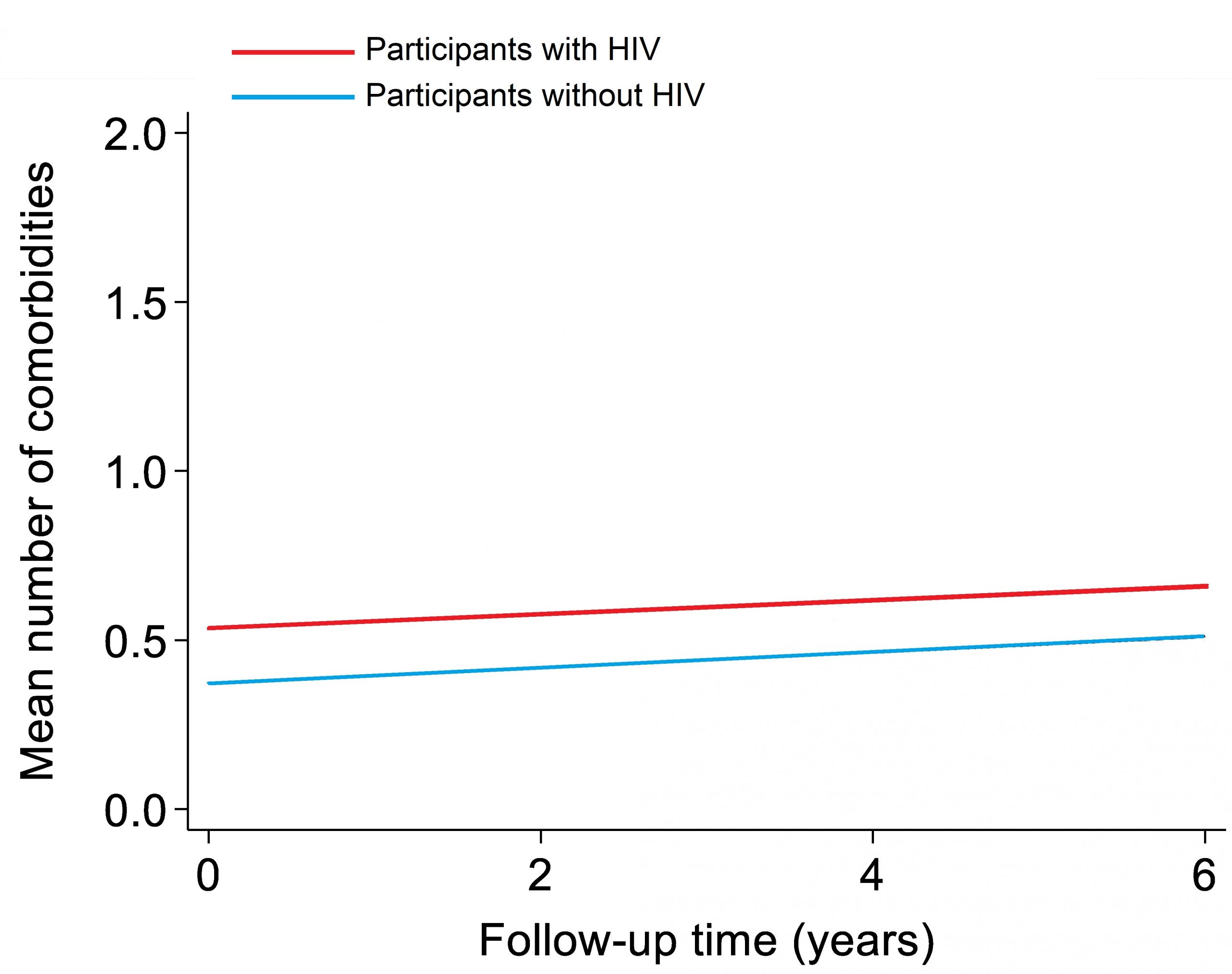

The main aim of the AGEhIV Cohort Study is to answer two questions. Firstly: do people with HIV develop additional diseases, so-called comorbidities, more quickly than people without HIV? And secondly: which risk factors play a role in this? Earlier research in our study already showed that participants with HIV do indeed have more comorbidities on average than participants without HIV. The comorbidities that are more common among participants with HIV are high blood pressure, myocardial infarction, narrowed blood vessels of the legs or abdomen, renal impairment, and reduced lung function. Until now it was unclear whether the difference in the number of comorbidities between participants with and without HIV increases over time as participants get older.

We have now investigated this by looking at the change in the average number of comorbidities. We compared this between participants with and without HIV over a six-year period. At the first study visit, the average number of comorbidities was higher in participants with HIV than in participants without HIV. Over time, participants from both groups developed more comorbidities. This increase was equally rapid in participants with and without HIV. This can be seen in figure 1: the red line (participants with HIV) starts and remains higher than the blue line (participants without HIV), but the lines rise at the same rate.

Figure 1

The risks associated with these comorbidities were also examined. It turned out that people with more comorbidities had a higher risk of dying. This higher risk of death was mainly due to cancer. This did not concern the cancers typical of AIDS (Kaposi’s sarcoma, certain types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and cervical cancer), but other cancers (such as lung, colon, anus, and liver cancer).

What does this mean?

The results of this study are partly reassuring. People with HIV who use successful antiviral treatment do not develop comorbidities at an accelerated rate as they age compared to people without HIV. So even though people with HIV had more comorbidities at the time the study started, the difference in comorbidities compared to people without HIV did not increase. Nevertheless, it remains important to prevent these comorbidities, to detect them at an early stage and to treat them in time. This certainly applies to the ‘non-AIDS-related cancers’ as well.

Do you want to know more? Click here for the article.

Risk of SARS-COV-2 infection

In February 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic started in the Netherlands, caused by the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Within the AGEhIV Cohort Study, the COVID-19 substudy started in September 2020. The aim of this substudy is to gain more insight into the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for people with HIV. The first topic that was investigated within the COVID-19 substudy was how many participants had contracted a SARS-CoV-2 infection in the period from February 2020 till April 2021. In addition, we investigated whether participants with HIV had a higher, equal or lower risk of getting infected with SARS-CoV-2 compared to participants without HIV.

In total, 13.4% of the participants with and 11.6% of the participants without HIV had a SARS-CoV-2 infection between February 2020 and April 2021. In comparison: this is approximately the same as the percentage of Dutch people aged 55 to 75 years who got infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the same period (source: RIVM, Pienter Corona Studie). In our study, participants with HIV did not have an increased risk of contracting a SARS-CoV-2 infection. Participants who were younger and participants of African descent had a higher risk of contracting a SARS-CoV-2 infection. The reason why is not entirely clear.

In addition, the amount of antibodies against the nucleocapsid (N) protein in participants who had experienced a SARS-CoV-2 infection, was examined. Antibodies against the N-protein of SARS-CoV-2, unlike antibodies against the spike protein, are only formed after natural infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The N-antibodies levels were similar between both groups of participants.

Altogether, this is good news for people with HIV. However, it is important to mention that, with a few exceptions, all our participants with HIV are well treated (i.e. undetectable virus and sufficient amount of CD4 T-cells). People with HIV with a detectable virus and few CD4 T-cells may have a higher risk of getting infected with SARS-CoV-2.

If you want to read more about this research, you can find the publication here.

Quality of life and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic

In September 2020, the COVID-19 substudy within the AGEhIV Cohort Study started. Besides a blood draw, participants of the COVID-19 substudy complete a questionnaire every six months. This includes questions on the social distancing measures, the use of alcohol, tobacco and recreational drugs, but also on the experienced quality of life and depressive symptoms. With the results of the questionnaire of the first study visit we investigated the change in these factors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The majority of participants indicated it was important to prevent getting an infection with SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (79.8%), the social distancing measures were important (77.4%) and they reported good self-adherence to these measures (66.9%). These percentages were similar in the group of people with HIV and without HIV. Also, a majority in both groups indicated that their use of alcohol, tobacco and recreational drugs did not change due to the COVID-19-pandemic.

Our study showed that participants who were worried about getting ill with COVID-19 and had three or more additional diseases beside HIV (comorbidities) reported a lower quality of life. In addition, participants who were worried about getting ill with COVID-19 and participants younger than 60 years had a higher chance of having moderate to severe depressive symptoms. These observed associations were similar for people with and without HIV, and living with HIV did not influence the quality of life and the chance of depressive symptoms.

Over all, a large proportion of the participants, irrespective of their HIV-status, reported good adherence to the social distancing measures during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. Living with HIV itself did not influence the quality of life or the chance of having depressive symptoms during the pandemic. Irrespective of their HIV-status, participants who were worried about getting ill with COVID-19 had a lower quality of life and a higher chance of moderate to severe depressive symptoms. So, it is important for everybody to pay attention to mental health during a pandemic and when social distancing measures are implemented.

If you want to read the complete article, please click here.

Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

SARS-CoV-2 vaccines became available in January 2021. We wanted to investigate whether the immune response to these new vaccines differed between people with and without HIV. Therefore, we asked participants of the AGEhIV COVID-19 substudy if they were willing to come in for an additional blood draw. That blood test was done 4 to 13 weeks after the last shot of their first vaccination series against SARS-CoV-2. That is, after two shots with Pfizer, Moderna or AstraZeneca and after one shot with Janssen.

Of the participants who decided to participate in this additional study, 66% had been vaccinated with Pfizer, 28% with AstraZeneca, 3% with Moderna and 2% with Janssen. We looked at the two types of immune responses, that can be expected after administration of vaccines. First, to the production of antibodies against the coronavirus (the so-called ‘humoral’ immune response). Secondly, to the activity of T-immune cells on SARS-CoV-2 virus particles (the so-called ‘cellular’ immune response).

The study showed that our participants with and without HIV responded equally well to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. We found no significant differences in their humoral immune response or cellular immune response after vaccination. Participants (both with and without HIV) who had already been infected with SARS-CoV-2 before their vaccination had a higher immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. This was a confirmation of other studies.

All in all, this is positive news for people living with HIV. It is important to mention that the participants with HIV in our study have effective HIV treatment: in most of them the virus is undetectable and most of them have sufficient CD4 T-cells. Other studies show that people with HIV who have an unsuppressed virus and few CD4 T-cells may respond less well to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

If you are interested in this article, click here.

HIV-medication and risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe COVID-19

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been speculated that use of certain HIV medications, including tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), etravirine, and integrase inhibitors (INSTIs), may protect against acquiring a SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or getting severe COVID-19, resulting in hospitalization or death.

Using the data collected from participants with HIV in the AGEhIV COVID-19 substudy during the period from February 2020 to April 2021, we also investigated whether there is a possible effect of HIV medication on acquiring a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

During that period, 29 of the 239 participants with HIV (12.1%) experienced a SARS-CoV-2 infection, which we found to be unrelated to the use of TDF, etravirine, INSTIs or other HIV drugs.

To investigate whether the use of certain HIV medications may protect against becoming seriously ill from COVID-19, together with colleagues from the HIV Monitoring Foundation (SHM), we examined data from the much larger national ATHENA-SHM cohort (https://www.hiv-monitoring.nl/en). The number of participants in the AGEhIV COVID-19 substudy with severe COVID-19 was (fortunately) far too limited to reliably answer this question.

The ATHENA-SHM cohort contains the data of the vast majority of people with HIV in care at one of the Dutch HIV treatment centers. Of the 2,189 people in the ATHENA-SHM cohort who used HIV medication and contracted COVID-19 between February 2020 and December 2021, 158 people got severe COVID-19: 149 people were hospitalized and 29 people died of COVID-19. Again, we found no association between the use of TDF, etravirine, INSTIs or other HIV drugs and the risk of developing severe COVID-19.

Our study does not provide any indication of a protective effect of certain HIV medications against acquiring a SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or developing severe COVID-19. It is therefore definitely not advisable to adjust the choice of HIV medication with this in mind. The full article can be read here.

Aging, HIV, and the immune system: not the same for everyone

The AGEhIV study has previously shown that participants with HIV are more likely to have age-related diseases compared to participants without HIV. To better understand why this is, we took a closer look at potential differences in, among other things, the immune system in a subset of participants.

We found, through blood tests, that participants with HIV had relatively more signs of an active thymus and fewer signs of inflammation compared to participants without HIV. Furthermore, these participants with HIV developed fewer age-related diseases over time, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and kidney function loss.

The thymus is a small organ in the chest that is responsible for the production of T-cells, a crucial group of white blood cells. Generally, as we age, the thymus shrinks, is replaced by fat tissue, and gradually loses its function. Our findings suggest that, for some of our participants with HIV, this process occurs more slowly, allowing them to continue producing new T-cells as they age and remain healthier longer.

Cardiac autonomic control

It has been known for some time that people with HIV have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Partly, this is due to general risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as smoking, obesity, high cholesterol, diabetes and sometimes hereditary factors. We also know that the presence of HIV plays a role. HIV causes chronic inflammation in the body, which remains present even with good use of HIV medication. From research among the general population, we know that chronic inflammation can disrupt the control of the nervous system on the cardiovascular system (this is also called cardiovascular autonomic control). And that this increases the risk of cardiovascular disease.

We measured cardiovascular autonomic control in all AGEhIV Cohort participants between 2016 and 2018 with a 10-minute blood pressure measurement. We compared the results of this measurement between AGEhIV participants with and without HIV. We know that these two groups do not differ greatly in terms of lifestyle factors that are known to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. To investigate the role of lifestyle, we also compared the measurements in our participants with those in participants of the HELIUS (HEalthy LIfe in an Urban Setting) study, who reflect the general Amsterdam population. We specifically looked at men between 50 and 70 years old of European descent to make the comparison between the groups as reliable as possible.

The study found that European male AGEhIV participants with HIV aged 50 to 70 years had, on average, slightly worse cardiovascular autonomic control than both AGEhIV participants without HIV and HELIUS participants. Among participants with HIV, men who had previously had more impaired immune function due to HIV (as determined by lowest CD4 count ever) now appeared to have more impaired cardiovascular autonomic control. This also applied to participants who had used the HIV medications stavudine, didanosine, zalcitabine or zidovudine in the past (and especially for a long period of time). Our results suggest that impaired cardiovascular autonomic control could be one of the explanations for the increased risk of cardiovascular disease we see in people with HIV.

For more information, click here